- Introduction

- History of Craft

- Current State of Craft

- The Future of Craft

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- List of Illustrations

Introduction

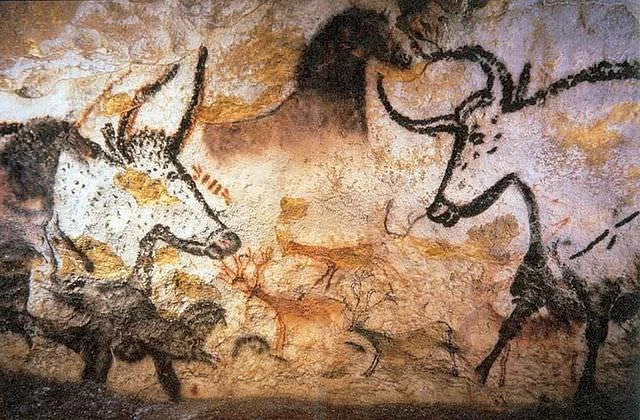

When discussing craft and making as an art medium, Tim Ingold said it best saying “I want to think of making […] as a process of growth” (Ingold, 2013, p.20). Craft itself as a practice has been an art form that has stood the test of time, starting as far back as lithic technology and cave paintings, and continuing forward to the present day experimenting with digital craft and robotics. However, the meaning of craft has changed as time has progressed and has evolved into a large sprawling variety of new formats and mediums. When designers/makers adapted to the changes to craft, so did the status of owning crafted, bespoke pieces which opened up the medium of craft and made it a whole new world. Through this essay I will inform you about the changes within craft and status throughout the past, present and future, explaining current trends and innovations with craft in today’s climate and how we can push ourselves in this industry to evolve into the future. I hope that it will provide some insight into the role of a designer/maker in the 21st century and how things will change in this field over the next 10 years and beyond.

History of Craft

In the beginning, the role of the designer/maker was limited to the usage of lithic technology, otherwise known as flint and obsidian tools, as well as Homo Faber constructs of jobs which majorly consisted of carpenters, fishermen, hunters and farmers. Craft as a recognised practice was anonymous in the early stages of human evolution and continued to be during historical periods such as Ancient Egyptians and Romans, due to enslavement and forced labour. The practice of craft itself wasn’t historically present until the artisan class was introduced in the Middle Ages, when medieval towns regulated the supply and demand of crafts and transitioned from Commerce to Mercantilism through the creation of merchant guilds. As the guilds grew in popularity, so did the art of craft which allowed the rise of the artist, during the Renaissance era, to commence. During this time, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Filippo Brunelleschi allowed the art of craft to take shape and pave the way for designers/makers to exist. It was also during this time that artist, Cennino Cennini, published the great work ‘Il Libro Dell’Arte’ (The Craftsman’s Handbook), which catalogued his life and times as an artist as well as materials and techniques employed by artists like himself in the fourteenth century. This work allowed for a greater understanding of the artist but also helped designers/makers better understand the art of craft and how it can be interpreted in their style of creation.

Craft as a practice continued to be the global norm of creating products and artistic forms until the introduction of the Industrial Revolution, where the medium of craft was overshadowed by the looming creation of mechanisation, mass production and the assembly line. When these processes were introduced, it began to make hand processes obsolete due to the efficiency of mass production but it also took away the worth of having something made for you by an actual person. “For it is not the material, but the absence of human labour, which makes a thing worthless” (Ruskin, 1849). However, the world adapted and made industrial processes the new norm, spawning the creation of factories and plantations around the globe with the shift from Mercantilism to Capitalism/Communism (depending on where you were situated). The increase in industrial production meant that the need for handcrafted products lessened overtime, which caused craftsmen and artists to rise again and form an arts and crafts movement which was an attempt to stern aesthetic deficiencies of industrial production by making products for the few not the many, but intended for the many and not the few.

Due to the balanced supply and demand for both bespoke, handcrafted products as well as industrial efficient production, companies within the modern era found that incorporating designers/makers to provide new aesthetics and designs to bring more soul and human nature to objects made primarily by machines through the efficiency of industrial production. One of these designers/makers, Herbert Read, helped this collaboration and the merging of these two processes by creating design principles that allowed for a practical solution to the division that existed between art and industry. Read talked about the problems that existed with the standards of production saying “The real problem is not to adapt machine production to the aesthetic of handicraft, but to think out new aesthetic standards for new methods of production.” (Read, 1935). Read himself was inspired by combining the aspects of handicraft of industry production rather than following in the mindset of Ruskin, who wanted to return to the fundamental aspects of handicraft with the styles and mannerisms of the Renaissance tradition of ornament. This combination of art and industry helped mould what Is now known as Industrial Design, the forefront of industrial production as well as the modern mindset of what designers/makers are being taught to understand and master to be able to be incorporated into both fields of artistic understanding and industrial production.

Current State of Craft

When it comes to discussing craft in the present day, there are many ways of interpretation of how it is perceived and used. One of the current trends used within craft is the knowledge of sustainability and being environmentally friendly concerning the materials and processes used in the creation of craft. Due to growing up with extended teachings about climate change and ways of improving the ecosystems of our planet, designers/makers have been brought up to be more environmentally cautious when it comes to what we make with our art. These mindsets range from creating pieces with recycled materials, and figuring out what processes are most environmentally friendly, all the way to dedicating full projects to creating large-scale pieces to bring awareness to specific causes that require support. An example of this is a piece created by Canadian artist Vong Wong, who created a large-scale plastic sculpture from reclaimed plastic to highlight the magnitude of plastic pollution. The sculpture itself embodied waves and was created to raise awareness about the impact of single-use plastic pollution on the world’s oceans, as scientists have predicted “If the current trend continues, there could be more plastic than fish (by weight) in the ocean by 2050” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). Designers/makers, such as Wong, who create art with sustainability in mind have allowed improvement in the creative mindset as well as allowed a way to create beautiful art pieces with a strong message of unity and helping the world become a better place for the future.

Another form of craft that is well-known in the present day is the supply and demand for bespoke objects. In today’s climate having something made for your needs and is uniquely made for you is something that sets you apart from everyone, giving you a form of elevated status that can allow for increased perception of yourself from others as well as stronger levels of confidence. Hermès is a great example of a company at the forefront of the creation of bespoke objects in the current craft world. They are an independent, contemporary artisan creator community who specialize in “the creation of useful, and elegant objects which stand the test of time”. They value creative freedom, sustainable development and providing a unique experience when discovering something that best suits your needs. Designers/makers who have found their calling and mastery of their chosen craft, much like the designers/makers apart of Hermès, have found beloved career paths down the route of the creation of bespoke objects as it allows the creation of their art to be more personal to the customer allowing a higher sense of achievement and having to ability to make someones dream a reality.

To allow increased use of sustainable materials, craft has evolved in recent years by incorporating itself with technology, such as Computer-Aided Design and 3D printing, to create a new branch of itself called Digital Craft. This form of craft has become increasingly popular with the latest innovations of 3D printing technology that have been introduced over the past decade, allowing it to become more accessible to be used in creative fields as well as creative studies. The use of digital craft allows for the ways of handcrafted pieces to be pushed beyond human capabilities while also possessing the designer/maker’s craftsmanship. An example of an artist well versed in digital craft is Henrik Mauler, a designer part of the collective known as Zeitguised, who mixes textile design with sculpture and algorithms to create uniquely structured pieces. When asked about the existence of digital craft, Mauler said the following:

Of course. Most people think you press a button and the machine produces the rest, but everything that is done with the help of computers is extremely handcrafted, it’s like glassblowing or model making. The linkability and manipulability must be worked out, and then something new emerges.

(Mauler, 2019 https://www.meisterrat.com/en/interview-zeitguised-was-ist-digital-craft/)

Having access to these art forms as designers/makers allows us to experiment with different material techniques that we never thought we would have access to, giving us the chance to figure out new ways of expressing our art and how we can showcase and push our skills and talents into the future of craft.

The Future of Craft

As designers/makers, we are always looking into new and innovative ways to pursue our craft and push our practice into the future. An innovative mindset can help push your work to the next level and a creative that has a unique innovative mindset is Professor of Design, John Wood. Wood himself explores new possibilities in design thinking, researching into topics such as synergy, systems theory and meta-design. Wood allows artists to adapt their mindset to new ways of thinking by bringing in new ways to express idea generation and decision-making within the context of a creative field. For example, Woods has talked about decision-making in such ways as:

Designers make daily decisions with regard to the use of resources, and to the lifestyle and use of products, places and communications. In order to achieve the needs of businesses, the desires of the consumer and improvement of the world, the designer in making decisions must embrace dimensions of social responsibility

(Wood, 2017, p.6)

Having these idea-generation techniques in your designer toolkit, it allows for your projects as a designer/maker to have added depth and understanding of complex themes as well as a deeper knowledge of problem-solving with the ability to see ideas from alternative perspectives. Being able to create a project from a variety of different ideas combined can help designers/makers of the future to be more innovative and allow their craft to carry more systematic understanding.

Another mindset to have when considering how to push your creative mindset as a designer/maker in the future of craft is using your practice to carry a strong statement as its purpose as opposed to having just a decorative purpose. This is where the ideology of Design Activism comes from, where the use of art & design shows collective change by people who share a common purpose and solidarity in sustained interactions with the authorizations they stand up against. Alastair Fuad-Luke is one of many artists whose values coincide with design activism. Fuad-Luke has written many books about design activism itself as well as other topics within his area of expertise such as sustainability and eco-design. Fuad-Luke goes on to define design activism as “design thinking, imagination and practice applied knowingly or unknowingly to create a counter-narrative aimed at generating and balancing positive social, institutional, environmental and/or economic change” (Fuad-Luke, 2009, p. 27). Using design activism as a mindset when considering the contextual understanding of projects as a designer/maker, will allow for a deeper statement to be seen within your work as well as being able to speak out about topics, such as politics and social issues, that you strongly believe in and should have more awareness brought to them.

However, design activism is a very broad ideology that can be used by a variety of art forms both inside and outside of craft when used by artists and designers/makers alike. Thankfully in 2001, Betsy Greer coined the term Craftivism (Craft+Activism) in the hope of creating more activism-based works in the medium of craft and being able to join minds within the craft community to bring other artists and makers together. With the help of 11 other artists, Greer was able to co-write a Craftivism Manifesto that expresses the values and meanings of what it means to believe in craftivism and what hopes the movement intends to produce. Greer incites what it takes to be a craftivist in this manifesto and what craftivism is capable of in many short passages such as:

Craftivism is about reclaiming the slow process of creating by hand, with thought, with purpose, and with love. Because activism, whether through craft or any other means, is done by individuals, not machines.

(Greer, 2017)

Hopefully, with the use of activism in the medium of craft, designers/makers will be able to stand up for the art of making and show in impactful ways what they believe in because “the art of making is important” (Greer, 2014, p. 8)

Conclusion

In conclusion, I believe that the role of the designer/maker is becoming more important in the present day and will become more impactful and innovative as the years progress. Over the next decade, I see this profession being at the forefront of inventing new ideas and concepts on how we can make the world better as well as creating pieces that speak impactfully about issues that need to be made right. The role of the designer/maker has stood the test of time and will always be needed and to emphasise this, I shall end with a quote from Diderot’s Encyclopedie which states:

CRAFT. This name is given to any profession that requires the use of the hands, and is limited to a certain number of mechanical operations to produce the same piece of work, made over and over again. I do not know why people have a low opinion of what this word implies; for we depend on the crafts for all the necessary things in life. The poet, the philosopher, the orator, the minister, the warrior, the hero would all be nude and lack bread without this craftsman, the object of their cruel storm. (Diderot, 1978)

Bibliography

Craftivism (2017) The Craftivism Manifesto.2.0. Available at: https://craftivism.com/manifesto/ (Accessed: 9th December 2020)

Cross, N. (2006) Designerly Ways of Knowing. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media

Diderot, D. (1978) Diderot Encyclopedia: The Complete Illustrations, 1762-1777. New York: Abrams.

Dormer, P. (1994) The Art of the Maker. London: Thames & Hudson

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2017) The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics & Catalysing Action. Barcelona: GAM Digital

Fuad-Luke, A. (2009) Design activism : beautiful strangeness for a sustainable world. London: Earthscan

Greer, B. (2014) Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press

Hermès (2020) About Hermès. Available at https://www.hermes.com/uk/en/story/271292-contemporary-artisans-since-1837/ (Accessed: 8th December 2020)

Ingold, T. (2013) Making: Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge

Johanssen, P (2019) Interview with Henrik Mauler, 26th January. Available at https://www.meisterrat.com/en/interview-zeitguised-was-ist-digital-craft/ (Accessed: 8th December 2020)

Kolko, J. (2012) Wicked Problems: Problems Worth Solving: A Handbook and Call to Action. Austin: AC4D

Locke, J. (2014) An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited

Read, H. (1935) Art and Industry: The Principles of Industrial Design. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company

Ruskin, J. (1857) The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Wisconsin: J. Wiley

Sennett, R. (2009) The Craftsman London: Penguin UK

Simon, H. (2019) The Sciences of the Artificial Cambridge: MIT Press

Walker, S. (2012) Sustainable by Design: Explorations in Theory and Practice. London: Routledge Woods, John (2017) Design for Micro-Utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible. London: Routledge

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: Ancient History Encyclopedia (2015) Cave Painting in Lascaux Available at: https://www.ancient.eu/image/3539/cave-painting-in-lascaux/ (Accessed: 7th December 2020)

Figure 2: Hyman, I. (2020) Filippo Brunelleschi: Italian Architect. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Filippo-Brunelleschi (Accessed: 7th December 2020)

Figure 3: Niiler, E. (2019) How the Second Industrial Revolution Changed Americans’ Lives. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/second-industrial-revolution-advances (Accessed: 7th December 2020)

Figure 4: Hitti, N. (2017) People’s Industrial Design Office uses as little material as possible to create wireframe Mesh Chair. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/09/14/mesh-chair-peoples-industrial-design-office-furniture/ (Accessed: 7th December 2020)

Figure 5: Suggitt, C. (2019) This amazing sculpture is made from thousands of recycled straws. Available at: https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2019/2/this-amazing-sculpture-is-made-from-thousands-of-recycled-straws-561097 (Accessed: 8th December 2020)

Figure 6: Hermès (2020) About Hermès. Available at https://www.hermes.com/uk/en/story/271292-contemporary-artisans-since-1837/ (Accessed: 8th December 2020)

Figure 7: Johanssen, P (2019) Interview with Henrik Mauler, 26th January. Available at https://www.meisterrat.com/en/interview-zeitguised-was-ist-digital-craft/ (Accessed: 8th December 2020)

Figure 8: Wood, J (2013) The creative quartet – a tool for metadesigners: John Wood at TEDxOslo 2013 Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=9dIQOrVhM5E (Accessed: 9th December 2020)

Figure 9: Design Indaba (2020) Design Activism. Available at: https://www.designindaba.com/topics/design-activism (Accessed: 9th December 2020)

Figure 10: Iqbal, N. (2019) ‘A stitch in time: how craftivists found their radical voice’, The Guardian, 28th July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/28/craftivism-protest-women-march-donald-trump (Accessed: 9th December 2020)